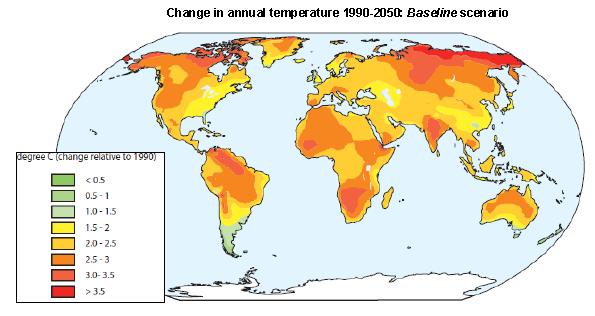

From Key Findings on Climate Change, THE OECD ENVIRONMENTAL OUTLOOK TO 2050 (forthcoming, 2012), Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

—————

“New figures from the U.N. weather agency Monday showed that the three biggest greenhouse gases not only reached record levels last year but were increasing at an ever-faster rate, despite efforts by many countries to reduce emissions.”

Seth Borenstein , Greenhouse gases soar; scientists see little chance of arresting global warming this century, Washington Post (Associated Press), November 21, 2011.

—————

Primary sectors such as agriculture, forestry and fisheries will be affected more severely than others. The attraction of tourist destinations will change. … Ski resorts at low and medium altitude could be affected by reduced snow cover …The likelihood of the development of extreme weather conditions will affect the insurance industry, which will be forced to pass on the rising cost of damages to other economic sectors … Jobs will be created in companies that can take advantage of opportunities created by climate policies and jobs will be lost in companies that cannot adapt.

Climate Change and Employment, European Trade Union Confederation.

—————

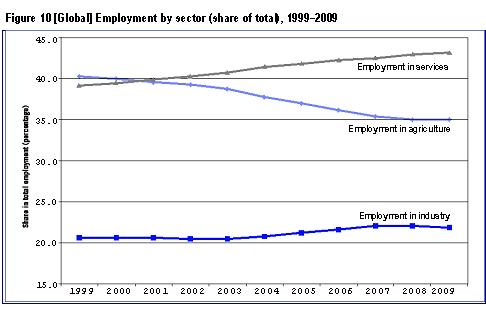

About 1.3 billion people, or 40 percent of the economically active people worldwide, work in agriculture, fishing, forestry, and hunting or gathering.

Human Development Report 2011, United Nations Development Programme.

———————–Comments———————–

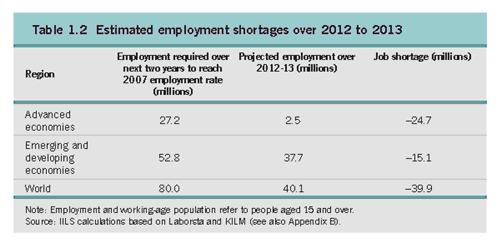

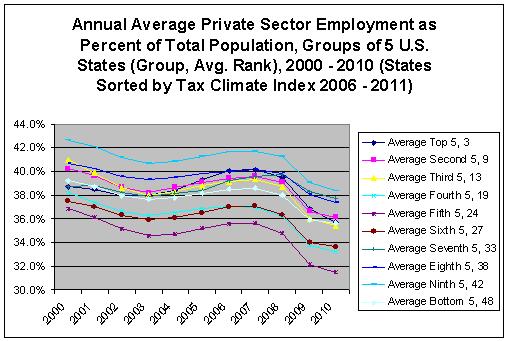

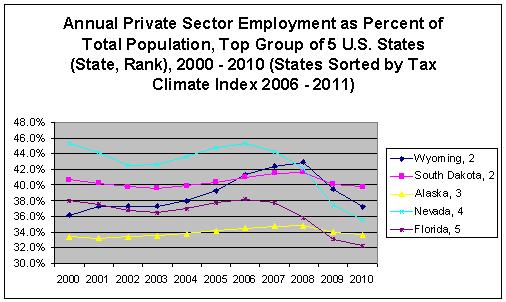

In recent decades, the world’s communities and working families have faced increasing employment and income instability as the pace of technological change and the pace of transnational capital transfers have increased. More and more communities see whole industries come and go; more and more working families now cope with recurring periods of unemployment and underemployment; increasingly, working people find themselves having to negotiate major job transitions (many of which require investments in retraining and many of which result in lower wages and benefits); larger numbers of workers become trapped in long-term unemployment.

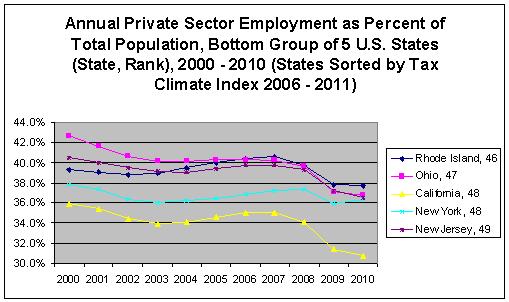

Climate change is adding to global employment and income instability through its impacts on the global distribution of investment opportunities and risks. Primary impact is on climate sensitive industries (e.g., agriculture, fisheries, forestry, tourism, insurance, health care — in response to changing disease threats, emergency services). Changing global weather patterns are transforming local and regional mixes of market opportunities, production and distribution costs, and risks to communities across the world. Older business models and technologies are being modified or abandoned and replaced with different business models and new technologies, and the responsibilities assigned to governments and non-profit organizations are being transformed, as the consequences of climate change accumulate.

The contribution of climate change to global employment and income instability extends well beyond the most climate sensitive industries. Weather is totalitarian: every aspect of our lives is affected to some degree by its patterns and changes, from housing codes to travel decisions, from clothing requirements to food choices, from health care requirements to leisure activity decisions. Thus, as the consequences of climate change accumulate, we will make large and small changes to the way we live.

In some parts of the world, the changes made will be substantial and rapid, generating newsworthy investment and employment upheaval. In other parts of the world they may be minor. But even minor individual changes, when made in a short time span, can aggregate into a force that unsettles business opportunities and demands made on governments.

Recent evidence suggests that climate change is accelerating. As it does, the consequences of climate change will accumulate more rapidly, awareness of the consequences will increase, and corporations and investors will accelerate their efforts to respond to consequences already felt and prepare for those just ahead. Global employment and income instability will increase all the more.