SOURCE ITEMS

The Employment Situation for January 2013 News Release (PDF Version), Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 1, 2013.

—————

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, January 20, 2013.

—————

Despite a moderate pick-up in output growth expected for 2013–14, the unemployment rate is set to increase again and the number of unemployed worldwide is projected to rise by 5.1 million in 2013, to more than 202 million in 2013 and by another 3 million in 2014.

Executive Summary, Global Employment Trends 2013, International Labour Organization, January 2013.

—————

As the global economy has gone from crisis to crisis in recent years, the cure has become part of the disease. In an era of zero interest rates and quantitative easing, macroeconomic policy has become unhinged from a tough post-crisis reality. Untested medicine is being used to treat the wrong ailment – and the chronically ill patient continues to be neglected.

Stephen S. Roach, Macro Malpractice, Project Syndicate, Sep. 30, 2012.

—————

The euro-area recession deepened more than economists forecast with the worst performance in almost four years as the region’s three biggest economies suffered slumping output.

…

The European data chimed with statistics in Japan, where the economy unexpectedly shrank last quarter as falling exports and a business investment slump outweighed improved consumption. GDP fell an annualized 0.4 percent, following a 3.8 percent fall in the previous quarter.

Marcus Bensasson, Euro-Area Economy Shrinks Most Since Depths of Recession, Bloomberg, February 14, 2013.

COMMENTS

Every year a spate of optimistic stories about the recovery from The Great Recession pour into American homes, offices and automobiles, as businesses and consumers rev up for the annual Season of Spending (and Hopeful Signs). This season begins with the returns to school in August and September and ends with the post-holiday sales in early January.

Soon after the Season of Spending ends, the optimistic stories begin to disappear as the economists and financial experts to whom writers and commentators in the media turn for information begin to grudgingly acknowledge that all is not well, after all, in the land of beautiful spending. The Season of Spending fades into memory and the artificially pumped up optimism of American business owners and consumers gives way to disappointment.

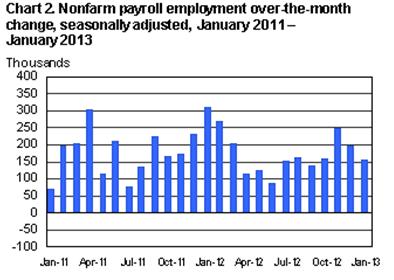

The annual cycle of positive and negative economic news is real, as the charts of over-the-month employment changes and quarter-to-quarter real growth in GDP illustrate[1]. But, the annual cycle of hope and disappointment is manufactured by influential economists and financial experts who either willfully ignore the flat trend line that cuts through the multi-year cyclical pattern, or worse, aren’t even aware of it. Ignore the underlying trend line and every fall time spending spree becomes a new “morning in America.”

Instead of pumping up optimism each fall on the basis of positive economic signals that are demonstrably temporary, economists and financial experts should be pointing out that job growth is not accelerating and explaining why the level of job creation remains well below the level needed to restore full employment and grow incomes. The trouble is, they can’t explain the trend line because it doesn’t make sense in traditional nation-centric models of employment growth.

The cyclical pattern of employment change in the U.S. is influenced by domestic spending, but the trend line around which U.S. employment change fluctuates is greatly influenced by world economic factors. U.S. employment trends are a subset of global employment trends, which are embedded in global economic processes, investment trends, and spending trends.

The world economy is limping along and recent reports strongly indicate that little improvement will take place over the next couple of years. GDP growth will be too slow to generate adequate employment growth, so unemployment and underemployment will rise. In this context it is wishful thinking to suppose that this spring will not bring another round of disappointment about job and income growth in the U.S.

[1] This pattern makes sense given the seasonal pattern of spending by Americans. The most difficult to resist pressures to spend are concentrated in the last five months of the year, the Season of Spending. Parents have to pay school fees and buy backpacks, computers, new clothes, and even cars for their children. During the holiday season, which follows close on the back to school season, spending increases because we all face powerful pressures from family and friends and advertisers, and because many of us have postponed optional spending until the holidays give us dispensation to empty out savings accounts and haul out the credit cards.