SEVEN ITEMS FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION

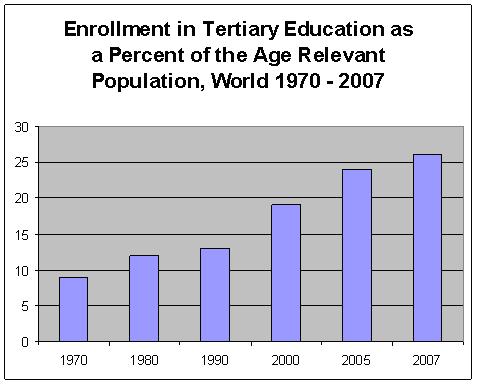

Data source: Global Education Digest 2009: Comparing Education Statistics Across the World, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2009.

Data source: Global Education Digest 2009: Comparing Education Statistics Across the World, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2009.

—————

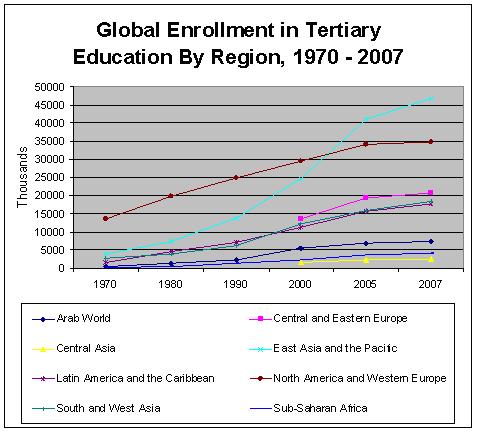

Data source: Global Education Digest 2009: Comparing Education Statistics Across the World, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2009.

Data source: Global Education Digest 2009: Comparing Education Statistics Across the World, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2009.

—————

“Companies no longer need to divide their skills strategies between high-cost ‘head’ nations employing-high skilled, high-waged workers, and ‘body’ nations that are restricted to low skilled, low waged employment. This change has come about via a combination of factors including the rapid expansion in the global supply of high skilled workers, in low-cost as well as high-cost economies, advances in information technologies, and rapid improvements in quality standards in emerging economies, including the capability to undertake research and development.”

Phillip Brown, Hugh Lauder, and David Ashton, Education, globalisation and the knowledge economy, Teaching and Learning Research Programme and Economic and Social Research Council, September 2008.

—————

“Unemployment is running at 14 percent and record numbers of people are emigrating in search of work. … Ireland’s pitch to China was its usual combination of low corporate tax rates, a well-educated work force of English speakers and ready access to the European Union’s market of 500 million people. The country’s technological skill, particularly in agribusiness and education, was also emphasized.”

Douglas Dalby, Ireland Makes Pitch to Official From China, New York Times, February 20, 201.

—————

“More people are losing the same gamble as a 33 percent jump in U.S. graduate school enrollment in the past decade … runs headlong into a weaker job market.”

Janet Lorin, Trapped by $50,000 Degree in Low-Paying Job Is Increasing Lament, Bloomberg, Dec 7, 2011.

—————

[IBM] stopped providing a geographic breakdown of its employees in 2009. At the end of 2008, U.S. staff accounted for 115,000 of its 398,455 employees, according to its annual report that year.

Beth Jinks, IBM Cuts More Than 1,000 Workers, Group Says, Bloomberg, February 28, 2012.

—————

“Tech drives the economy, but it doesn’t drive employment. ‘We are a 100-person company and we serve 50 million people. That kind of leverage has never existed before,’ said Drew Houston, co-founder of the start-up Dropbox, a service that stores and shares digital files.

Nick Bilton, Disruptions: In Davos, Technology Moves Center Stage, New York Times, January 29, 2012.

COMMENTS

The assertion that a major impediment to economic growth and reducing unemployment and underemployment is a mismatch between the knowledge and skills most workers have and the knowledge and skills corporations are seeking is repeated often in the media and is widely accepted as true. Thus, calls for investing in the higher education programs that will create a workforce with the newer and higher end knowledge and skills the corporations want are also common.

The policy experts who make the skills mismatch assertion base it on reports by business leaders that they have a hard time filling certain positions. Unfortunately, those policy experts make the mistake of generalizing from a sample of workforce recruiting situations that is not at all representative of the larger population of U.S. recruitment situations.

Three reasons shortages of high end workers are not representative:

- They are almost always geographically localized, concentrated in particular industries, and relatively short term

- They evolve and move from place to place, but they never disappear; they develop when and where innovation is successful and reflect the nature of the innovation

- On an ongoing basis, they account for only a small part of the overall demand for high end workers.

Those policy experts also make the mistake of drawing artificial national and sub national boundaries around workforce recruitment activities, ignoring the fact that a growing proportion of the world’s corporations, including smaller domestic corporations now recruit globally. (And new evidence shows that corporations, not small businesses, account for the bulk of job creation and job destruction — see Floyd Norris, Small Companies Create More Jobs? Maybe Not, New York Times, February 24, 2012. )

The Global Problem

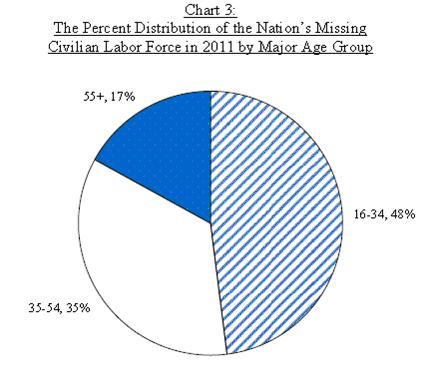

For the world economy as a whole, the salient shortage is the other way around: high end workers face a shortage of opportunities to put their educations and skills to work in good jobs (living wages and adequate benefits, safe working conditions, socially beneficial products and services). And this mismatch between the supply of high end workers and the demand for their knowledge and skills is getting worse.

The key factors:

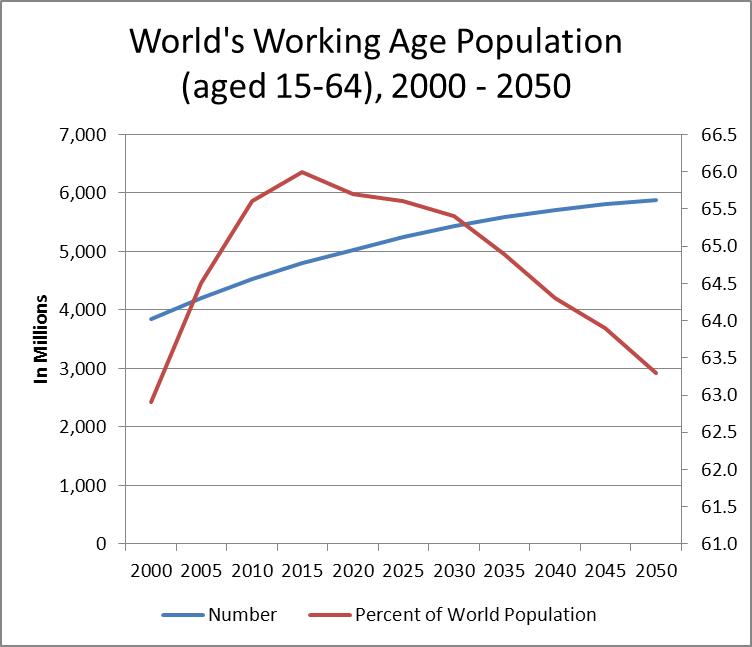

- Global demand for highly educated workers is growing very slowly because the world economy as a whole is growing very slowly;

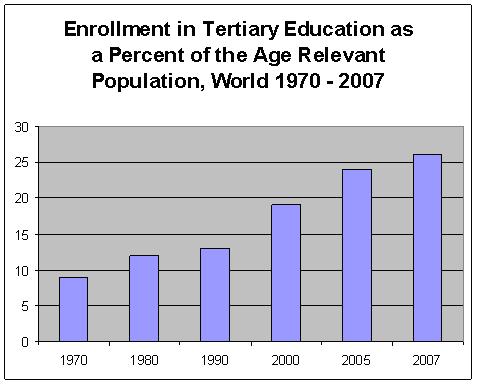

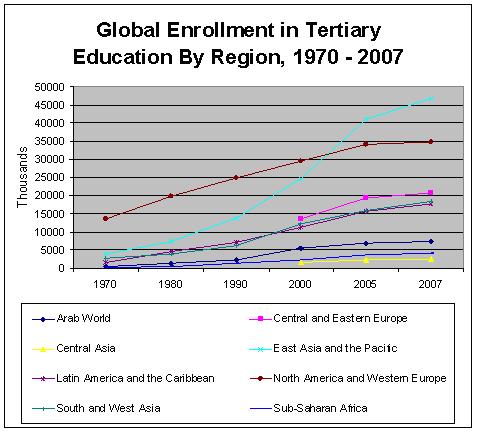

- The global supply of highly educated workers is increasing rapidly as nations, states, provinces, and cities invest in education as a way of competing for the business investments that generate good jobs

- Businesses of every size and in every economic sector pursue competitive advantage by investing in newer technologies than can now do the kinds of communications, evaluation, and decision-making work that most college educations prepare people to do.

Education is a good in and of itself, but global investing in higher education will not solve the long term problems of high unemployment and declining wages and benefits in the world economy. Public investments in education address the supply side of the global labor market equation, but unemployment and underemployment in a world with an expanding population of workers, including well educated workers is fundamentally a demand side problem.

U.S. Public Policy Dilemma

Again, education is a good in and of itself, but more U.S. investments in higher education will not pay off in better jobs and growing incomes for U.S. workers. The reasons are tied to extensive U.S. engagement in the world economy:

- Investments in higher education produce high end workers who become part of the global supply of high end workers; the skills and knowledge of those workers are available not only to U.S. corporations but to the competitors of U.S. corporations

- Those investments also put more downward pressure on high end wages and benefits in the U.S. because they add to an already excessive global supply of high end workers available to U.S. corporations

- Investments in programs that increase the demand for high end workers (big government investments in transitioning to green energy sources is often proposed) don’t increase demand only for U.S. high end workers; not only do U.S. corporations outsource work and recruit lower cost workers from other countries, so too do government agencies.

U.S. workers will get more employment opportunities and wage growth from investments in higher education only if the global demand for high end workers is brought into balance with the global supply. U.S. policy makers, acting alone, cannot cause this to happen. A much higher level of global management of investments in higher education, investments in job creation programs, and investments in income supports for working people whose labor is not needed is required.

A good model for this is offered by federal government management of the supply and demand for workers in the in the U.S. 1950’s and 1960’s.

In those decades, federal investments in higher education increased substantially, but it also made large investments in job creating programs – notably, investments in the development of military technology, in an ambitious space program, in research across the spectrum of intellectual fields, in new regulatory programs, and in community jobs programs. It also expanded income supports for workers not easily absorbed into the labor force because of disabilities, age, and skill limitations.

Thus, while higher education investments increased the demand for high end jobs, other government investments increased the supply of high end jobs, low end jobs in both the public and private sectors, and moderated the overall demand for jobs.

U.S. policy makers could and should lead in implementing this model for managing labor force development in the world economy as a whole. That would serve the interests of U.S. working families. But they cannot even fully participate in such an effort because American voters believe strongly in American exceptionalism and have an associated strong dislike for multinational government institutions (and for government involvement in economic matters in general). And that is a real dilemma.