ITEMS FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION

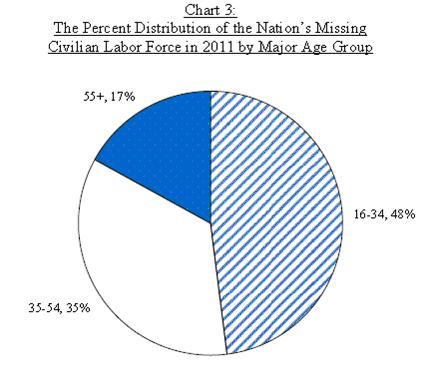

“Following 2007, the pool of hidden unemployed has risen steadily and strongly from 4.7 million in 2007 to close to 6.5 million in 2011; a rise close to 1.8 million or 40%. This was the third largest annual average number of hidden unemployed in the 45 year history for which such data exist dating back to 1967.”

Andrew Sum, Mykhaylo Trubskyy, with Sheila Palma, The Great Recession of 2007-2009, the Lagging Jobs Recovery, and the Missing 5-6 Million National Labor Force Participants in 2011: Why We Should Care, Northeastern University Center for Labor Market Studies, January 2012

—————

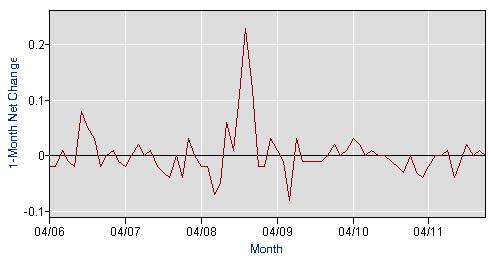

Change in Average Hourly Earnings of U.S. Employees, 2006 – 2011

Source: Historical Data, Current Employment Statistics, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Historical Data, Current Employment Statistics, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

—————

“Spain’s jobless rate for people ages 16 to 24 is approaching 50 percent. Greece’s is 48 percent, and Portugal’s and Italy’s, 30 percent. Here in Britain, the rate is 22.3 percent, the highest since such data began being collected in 1992. (The comparable rate for Americans is 18 percent.)

Thomas Landon, For London Youth, Down and Out Is Way of Life, New York Times, February 15, 2012

—————

Looking at the changes within countries over time, the overall long-term trend is obvious: the majority of countries have witnessed increases in low-wage employment over the past 15 years. Overall, figure 20 shows that, since the second half of the 1990s, low pay has increased in about two-thirds of countries for which data are available (25 out of 37 countries). … While it is too soon for an assessment of the short-term effect of the crisis on low pay (since few countries have published their data on low pay in 2009), there is little reason to believe that a global recession will have brought about any improvement in the overall situation of low-paid workers.

Global Wage Report 2010/11: Wage policies in times of crisis, International Labour Organization, December, 2010

COMMENTS

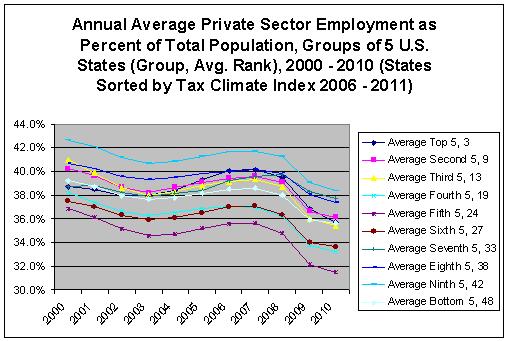

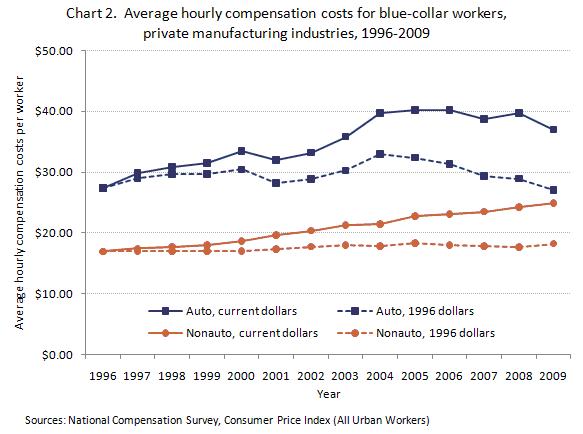

In a free market economy, buyers and sellers negotiate prices. When buyers have lots of choices and sellers don’t, buyers have the leverage to push prices downward.

We have seen this in the U.S. housing market: huge numbers of houses are on the market and an army of builders are waiting in the wings to put even more houses on the market – the ratio of sellers to buyers is very high. Thus, even though houses are beginning to sell a little better, prices are still falling.

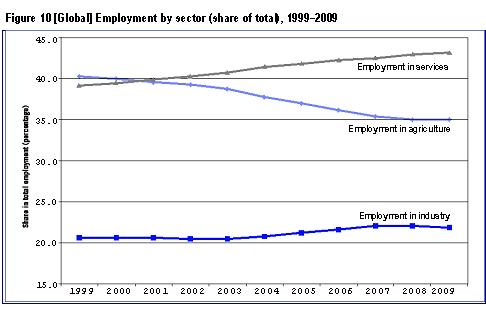

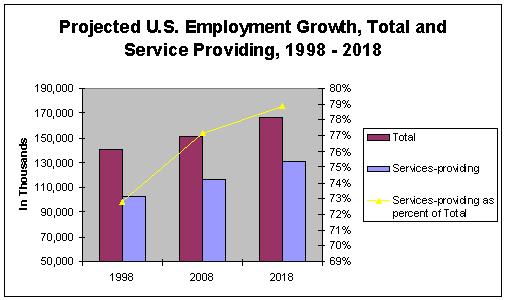

The same thing has happened in the global labor market: the ratio of available workers (sellers) to employers with jobs to fill (buyers) is very high, and it will stay high. There are several structural reasons:

- the integration of national economies into a single world economy based on free market principles has made huge numbers of unemployed and underemployed workers newly available to the world’s major employers and many intermediate size employers

- expanding national education systems are producing a growing supply of skilled workers for the global labor market

- the global economic crisis of 2008-2009 produced large numbers of business failures and consolidations, reducing the number of employers competing for the growing global supply of workers

- the production of a given volume of goods and services continues to require fewer and fewer workers as machines and computers do more of the brute work and more of the routine thinking

- global consumption of goods and services is not growing fast enough to reduce the ratio of available workers to available jobs.

Thus, even though hiring in the U.S. is beginning to get a little better, the bargaining position of U.S. workers, even those who are unionized, continues to deteriorate. Given this trend, either real U.S. wages and incomes will decline much further, or rates of unemployment, underemployment, and non-participation of working age people in the workforce will remain high.