ITEMS FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION

“’There is a separation between the United States economy and stock prices,’ said Russell Price, a senior economist with Ameriprise Financial. He said in 2008, a lot of the market momentum came from sales growth overseas in emerging markets, and a weaker dollar that helped profits.”

Christine Hauser, S.&P. 500 at Highest Close Since ’08, New York Times, February 24, 2012.

__________

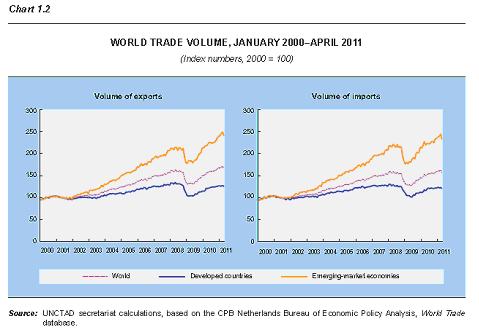

“Globalization is one factor driving up profit for companies in the United States. According to a March 2011 paper by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, foreign earnings represented 40 percent to 45 percent of total profit between 2008 and 2009, against around 20 percent in the 1980s.”

Martin Hutchinson, U.S. stock bubble is in profit, not value metrics, Reuters Breakingviews, March 5, 2012.

__________

A recent Standard & Poor’s study found that 50 percent of sales by companies in the S.&P. 500-stock index are outside the United States. Interestingly, the report also found that these companies paid more in foreign taxes than to the United States government. ”

Steven M. Davidoff, Tax Policy Change Would Bring Cash Piles Abroad Back Home, New York Times, August 16, 2011.

__________

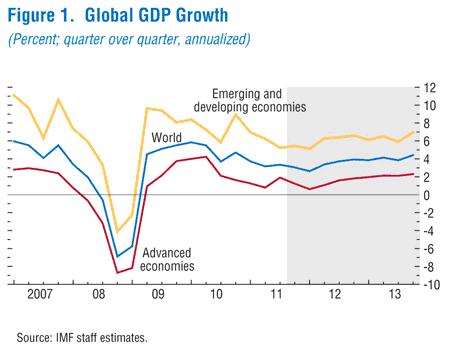

“China’s economic growth may further slow in the first quarter to 8.5 percent, from 8.9 percent in the fourth quarter of 2011, with the potential risks of a sharper global deterioration and a sudden domestic property downturn raising the government’s concerns about policy changes, a senior economist from the State Council’s think tank said on Thursday.”

Chen Jia, Economic growth could slow further, China Daily, March 23, 2012.

__________

“After a decade in which GDP rose by at least 9% a year, it slipped back to ‘only’ a bit above 8% by the end of last year, according to the OECD. For the next decade, the OECD forecasts annual growth will hover at around 7%.”

Brian Keeley, How Slow Will China Go?,OECD Insights, March 21, 2012.

__________

The difficulties in the euro area have affected the U.S. economy. … In addition, weaker demand from Europe has slowed growth in other economies, which has also lowered foreign demand for our products.

Ben S. Bernanke, The European Economic and Financial Situation, Testimony Before the Committee on Government Oversight and Reform, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C., March 21, 2012.

__________

A main indicator of business sentiment in Europe unexpectedly fell deeper toward recession territory Thursday, compounding concerns about the global recovery after signs of slowing manufacturing in China.

…

The survey of purchasing managers in the Chinese factory sector, released by HSBC, showed that activity declined in March for the fifth consecutive month, as the Chinese economy felt the pain of feeble global economic activity.

China has become a major market for European products as varied as heavy machinery and luxury goods, so a slowdown there worsens problems in Europe.

Jack Ewing and Bettina Wasserner: Indicators Fall in China and Europe, New York Times, March 22, 2012.

COMMENTS

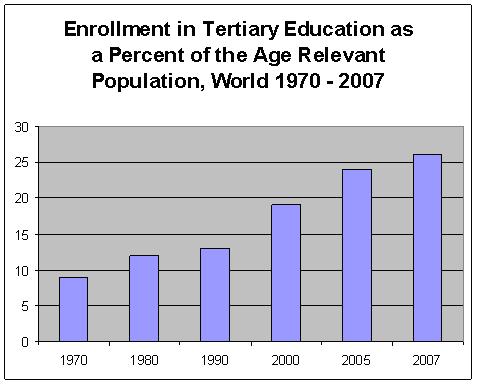

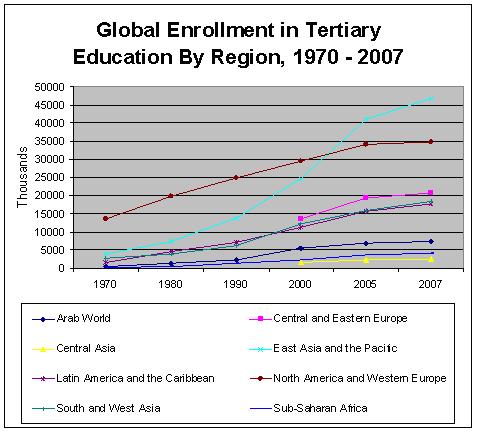

U.S. job growth is becoming more vulnerable to economic troubles that develop beyond the borders of the U.S. because U.S. corporations increasingly earn their profits in multiple regions of the world economy, perhaps not even primarily in the U.S. This trend can be expected to continue as high end manufacturing, investments in science and technology, and populations of affluent consumers continue to grow in Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa (referred to as BRICS) and spread to more countries.

The global distribution of U.S. corporate profit centers links economic troubles elsewhere in the world economy to U.S. job growth in two ways: through the impact of those troubles on the investment decisions of U.S. corporations and through their impact on incomes of older Americans.

Adverse Impact on Corporate Investments in the U.S.

With their economic interests spread across the world economy, economic troubles outside as well as inside the U.S. reduce the funds U.S. corporations have to invest anywhere. Wherever economic troubles arise, U.S. corporations are largely free to distribute losses across multiple parts of their worldwide operations in whatever combinations they deem most profitable.

The U.S. is very likely to get a share of investment losses, even those losses that originate outside the U.S. This is likely for at least two reasons:

- In recent years rates of return on investments have generally been higher in some of the emerging economies than in the U.S., so U.S. corporations are unlikely to favor the U.S. over all other countries in which they have operations.

- With an eye to future possibilities, U.S. corporations may even respond to shrinking profits outside the U.S. by shifting funds from the U.S. to economically troubled regions to maintain political favor, increase the productivity of operations in those regions, and/or finance takeovers of weaker competitors.

A reduction in the flow of investments in the U.S. almost necessarily slows job growth.

Adverse Impact on Spending by Older Americans

Economic troubles outside the U.S. can have an adverse impact on spending by all Americans, but the adverse impact on spending by older workers and retirees is particularly direct. Moreover, the size of the impact is growing as large numbers of baby boomers transition out of the labor force. (The Pew Research Center estimates that about 10,000 people now turn 65 every day. )

Older Workers. Older workers see retirement coming, so they are likely to increase investments for retirement. Those with families are also likely to try to build investments to leave their children.

Increases in investment activities link the spending behavior of older workers directly to economic troubles outside the U.S. because decisions about how much income to invest are influenced by stock market trends. And those trends are tied to profits earned by U.S. corporations outside the U.S. as well as those earned in the U.S.

To reach a given financial position, higher stock market returns translate into being able to keep more income for spending. Lower returns translate into having to reduce spending and invest more income. (In this regard, it is important to note that the majority of older workers are at the highest income plateau they will reach in their working lives, so investment increases must be offset by spending reductions.)

By lowering the rate at which stock values increase, troubles outside the U.S. reduce spending in the U.S. Less spending translates into slower job growth.

Retirees. The link between economic troubles outside the U.S. and the spending behavior of retirees is even stronger.

Retirement brings a partial or complete shift to sources of income that are quite dependent on trends in corporate profits and stock values – social security, pensions, and government programs that supplement incomes (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, assistance with food, transportation, and housing costs). Pensions are directly funded by corporate profits and stock values. Social Security and other government programs are funded by revenues partly derived from taxes corporate profits and taxes on individual earnings on stock portfolios.

Thus, through their adverse impact on corporate profits and stock values, economic troubles outside the U.S. reduce spending by U.S. retirees and government spending on behalf of retirees. Slower job growth necessarily follows.

The Longer View

Most economists keep looking for a much needed shift to a sustained high rate of job growth in the U.S. It probably will not come.

As things now stand, the world economy is chronically unsteady, plagued by sporadic outcroppings of economic troubles (that are mistakenly defined in terms of national boundaries rather than in terms of the world economy). U.S. job growth is dampened by this global and revolving economic troubles account and will be dampened further as U.S. corporations spread their operations to even more regions of the world economy.

This state of things is more likely than not to continue indefinitely, unless the world’s nations do a much better job of managing the world economy as a whole and the U.S. government does a better job of managing investments in the U.S.